Frida Kahlo is one of the 20th century's most famous artists, but the vast majority of the public knows nothing about her beyond her notorious unibrow and iconic self-portraiture. But who really was the artist behind all the fame? How did she live? What inspired her? How did she engage with politics and the world around her? How did she create?

These questions are what “Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) seeks to delve into. The show marks the MFA’s first Frida Kahlo show, which includes eight of Kahlo's paintings alongside more than 40 examples of Arte Popular, or Mexican folk art. The term “Arte Popular” was invented a year after the Mexican Revolution in 1920 and served as a bridge between artists and the government as a means to develop a national identity during turbulent political times. Kahlo and her inner intellectual circle relished these works as examples of Mexican national culture, or "mexicanidad." This is evident not only through how Arte Popular objects inspired her paintings, but also how Kahlo often styled herself, combining different pieces of indigenous clothing. The exhibition follows five thematic sections: Art of the People/Arte de Pueblo; Aesthetics of Childhood/Estéticas de la Infancia; Painted Miracles/Milagros Pintados; Living Still Lifes/ Naturalezas Vivas; Invented traditions/Tradiciones Inventadas; and an extension of the Graciela Iturbide’s current photography exhibition at the MFA, entitled "El Baño de Frida"(2006).

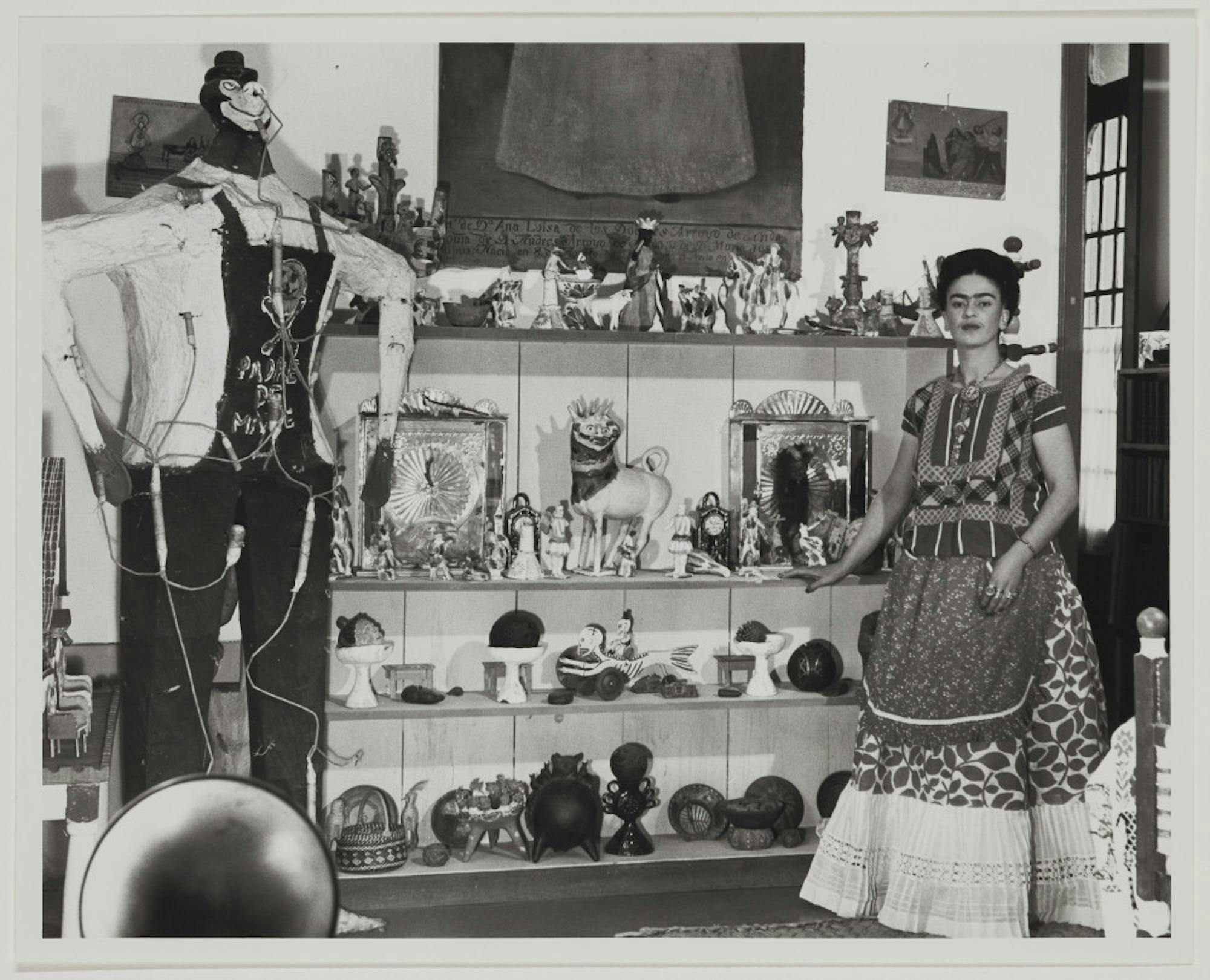

Upon entering the exhibition, viewers come face-to-face with “Judas” (2018), an eight-foot-tall replica commissioned by the MFA of Kahlo’s own papier-mâché Judas. The work was created by Leonardo Linares, whose grandfather, Pedro Linares, created many papier-mâché sculptures for Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Viewers will also see Dos Mujeres (Salvadora y Herminia) (1928), the MFA’s recent acquisition that sparked this exhibition. The painting is the beginning of the “Art of the People” section of the show, which features another Kahlo painting, “Self-Portrait of a Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace” (1940) alongside works of Arte Popular featuring nature and animals. The dual-dimensions and dense foliage of the folk works pairs exquisitely with Kahlo’s own work which features Mexican flora, fauna and people. Arte Popular was a reclamation of Mexican identity by everyday Mexican people, which was then appropriated by the revolutionary intellectual class to which Kahlo belonged.

The "Invented Traditions" section of the show addresses the role of folk art and traditional clothing in reclaiming Mexican indigenous identity. This section of the show is particularly beautiful, as it features both indigenous Mexican garments alongside pristine photographs of Kahlo and intellectual publications that feature Kahlo.

As the MFA's press release notes, “Just as Kahlo used paint to create pictures, she used clothing to create her own image. Garments, headdresses and accessories from Mexico’s rural and indigenous communities became her most visible collection of Arte Popular, worn during international travels and immortalized in photographs.”

The room is painted a deep red color, echoing the rich red tones of the garments as they hang delicately in space. Another section that feels incredibly delicate is "Living Still Lives", which focuses on Kahlo’s still-life works. The MFA also features folk art pieces depicting fruits and vegetables, and their vibrant colors are reflected in Kahlo’s work. The isolation of each Arte Popular object allows the viewer to concentrate on the unique details of the works.

They often take a lifelike quality, as noted in the press release: “She painted fruits and rocks as though they had eyes, skin and feelings, giving them humanlike qualities that are also visible in many works of arte popular.”

The other sections of the show, "Aesthetics of Childhood" and "Painted Miracles," also follow the same fusion of Mexican folk art and tradition that Kahlo often reinvented and made her own. The works are poignant enough to warrant intensive analysis and rumination by viewers. Overall, the show proves cohesive, and each section naturally relates to each other and Kahlo’s milieu.

Adjacent to "Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular" is an extension of "Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico,” entitled “Frida’s Bathroom." According to the press release, when Kahlo died in 1954, her grieving husband Diego Rivera locked all her personal belongings in a bathroom in Casa Azul. Fifty years later, the bathroom was opened to the public, and Iturbide was commissioned to photograph it. The photos are hauntingly intimate and expand on how Kahlo’s collection of objects shaped her life and her work.

In a time where 85 percent of artists featured in U.S. museum collections are white, and 87 percent are male, shows like “Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular” are more important than ever. Even more so, the MFA’s acquisition of Kahlo’s work is a small but positive step towards creating art spaces that represent all types of artists, rather than just white men. It also gives precedent to a type of art that has often been excluded from major museum collections and gives viewers the opportunity to engage with works they often do not engage with in these institutions. Iturbide's work in conjuction with Kahlo’s show is a great move and echoes the sentiment that Kahlo and her work paved the way for future female artists. She continues to inspire not only Mexican women and artists, but anyone who is lucky enough to encounter her work.

'Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular' marks MFA's first show dedicated to the legendary artist

"Frida Kahlo in Rivera Living Room with Figure of Judas" Bernard Silberstein (American, 1905–1999)

around 1940. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Gift of the artist. Bridgeman Images.

Detroit Institute of Arts.

Summary

"Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular" is a truly beautiful and poetic appreciation for Kahlo's work and Mexicanidad

5 Stars