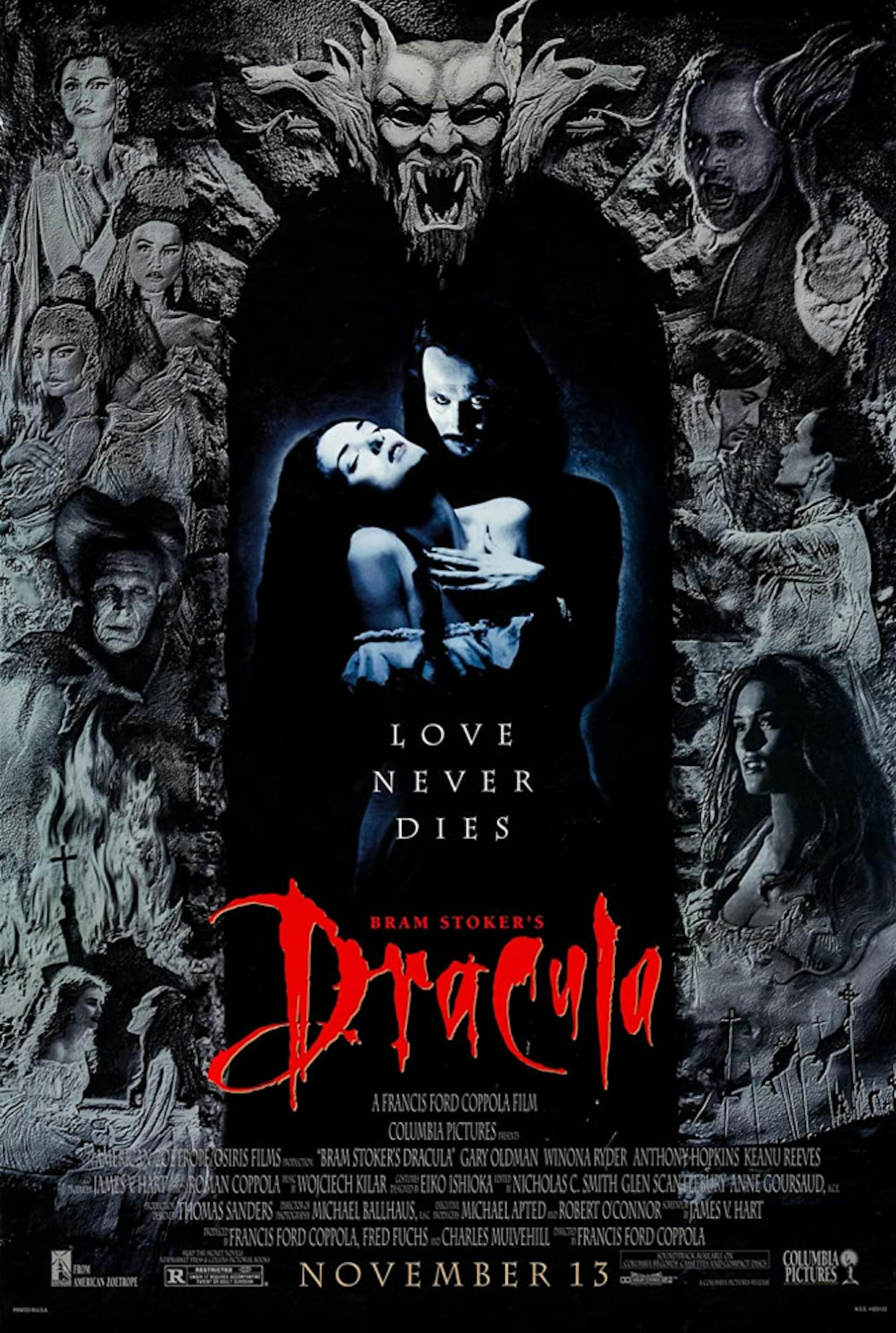

Bram Stoker’s "Dracula” (1992) is as much an anachronism as its title character. Directed by cinematic legend Francis Ford Coppola — whose storied filmography includes the oscar-winning “Godfather” films (1972, 1974 and 1990) and the Vietnam-era epic,“Apocalypse Now” (1979) — the film features an all-star cast, sprawling sets and a meticulously constructed turn of the century aesthetic.

Coppola famously eschewed digital or computer-generated effects for the film and insisted on practical and in-camera effects, drawing upon decades of old Hollywood movie magic to create a world that feels right at home in the time period in which the story takes place. Using everything from detailed miniatures and double exposure to running film footage backward, the effects create a film that is aided by nearly a century of progress and one of the most talented directors of all time to weave a unique look and design. To borrow an expression, they just don’t make films like Bram Stoker’s "Dracula” anymore, and often for good reason seeing as many of the effects require specific lighting, complex mirror work and each require hours upon hours to construct each intricate shot. The ability to tangibly know that everything on screen is something tangible means that even if the illusions aren’t totally convincing, there is a sense of craftsmanship that begs to be admired. Additionally, the sets and costumes are free from distracting anachronisms and immerse the actors into the world as much as the viewer, with the dark castle of Dracula seeming to swallow protagonist Jonathan Harker or the streets of London which feel lived in and vibrant. The details give the actors a great environment to immerse themselves, which allows the viewer to be drawn in alongside them.

The ensemble is, for the most part, stellar and gives most of the cast at least a few moments of spotlight each. The unfortunate elephant in the room, though, is Keanu Reeves as protagonist Jonathan Harker whose English accent feels as though he’s mixing his lines with his surfer dude character from the “Bill & Ted” franchise (1989–). The side effect of this is that Reeves’ Harker ends up feeling like a limp protagonist and the film loses the original underlying story of an ordinary man slaying a corrupting force. Acting opposite Reeves is his on-screen bride Mina Harker, portrayed by Winona Ryder with a sort of vulnerable courage that she would channel years later as Joyce Byers in Netflix’s “Stranger Things” (2016–). Gary Oldman is a scene-stealer as the fiendish count, oscillating between the more traditional cackling count when in Transylvania and morphing into a slick and seductive predator when he relocates to London. Anthony Hopkins portrays Professor Abraham Van Helsing with a jovial enthusiasm that masks a fierce edge and a razor wit. Even bit parts like Dracula’s assistant Renfield, played as a lunatic reveling in his own madness by Tom Waits, drip with charisma and presence and show that each member of the cast is pushing their acting to its absolute limit.

Famously, the film adds a romantic angle to the story, which begins in a prelude sequence narrated by Van Helsing that describes the rise and subsequent fall that led Vlad the Impaler to become Count Dracula. Each battle in Dracula’s campaign is told using shadows against a setting sun,representing the darkness that is slowly eating away at the God-fearing crusader. The moment where Dracula discovers his dead bride Elisabeta (also played by Ryder) is a powerful explosion of emotion as the count renounces God, stabs a nearby crucifix and begins to drink the phantom blood that runs from it. The introduction feels appropriately mythic, and yet the focus on medium shots gives the action an intimate feeling that strikes a nice balance between the two extremes.

Oldman’s Dracula is two-sided, one half feels more like a force of nature than anything else, a sort of invading force that threatens to upset the established order, powerfully exemplified by the scene that depicts Dracula’s journey to England. A storm rages over London and all of the city’s inhabitants feel the coming malevolence; Mina and her friend Lucy frolic in the rain and even share a kiss as a spectral image of Dracula’s face appears over them and smiles with perverse joy, animals in the zoo scream in terror and the inmates of the local insane asylum are whipped into a frenzy until the storm subsides and Dracula escapes his boat in the form of a wolf. The scene sets the viewer on edge, Dracula’s presence is in some ways liberating, but is translated into pure chaos in other respects, throwing the viewer into the same confusion as the characters.

Conversely, Dracula’s more human countenance, which he uses when he walks around London in the day, skews closer to his appearance in the prelude, a handsome figure who moves with great poise and control that disappears as soon as he encounters Mina in person. Mina, who looks identical to his fallen bride, clearly stirs something in the immortal as Dracula loses his composure momentarily, seeking words and stuttering as he encounters the face of his lost love. There’s pain in his awkwardness, and despite his mystical powers at night, the daylight allows the viewer to see the part of him that still remains human. These layers of dramatic complexity, thanks to both the script and the excellent chemistry between Ryder and Oldman, makes Dracula out to be more than a monstrous antagonist; he is also a man who fell from grace and wishes to reclaim a happier time. The film uses this unexpected humanity to make the viewer question: Just who am I rooting for, Harker, or Dracula?

Bram Stoker’s "Dracula” is a film that embraces the strangeness of its source material, keeping in odd and fantastical elements that might alienate some audiences and utilizing them to create an atmosphere of nightmarish, gothic surrealism. The film is a must-see for fans of classic movie-making techniques, or those looking for a traditional yet also somehow strikingly modern take on one of cinema’s finest monsters.