Bert Huang, assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science, hosted the first event in a series of seminars titled, "Making Real-World Data Science Responsible Data Science" for computer science students on Oct. 7. The series is run by the National Science Foundation-funded T-TRIPODS Institute, a multi-department, interdisciplinary effort across Tufts University that focuses on data science.

"The main theme of the seminar series is that it will feature people who have crossed disciplines to enact real policy or action to ensure safety of data science technology,” Huang wrote in an email to the Daily.

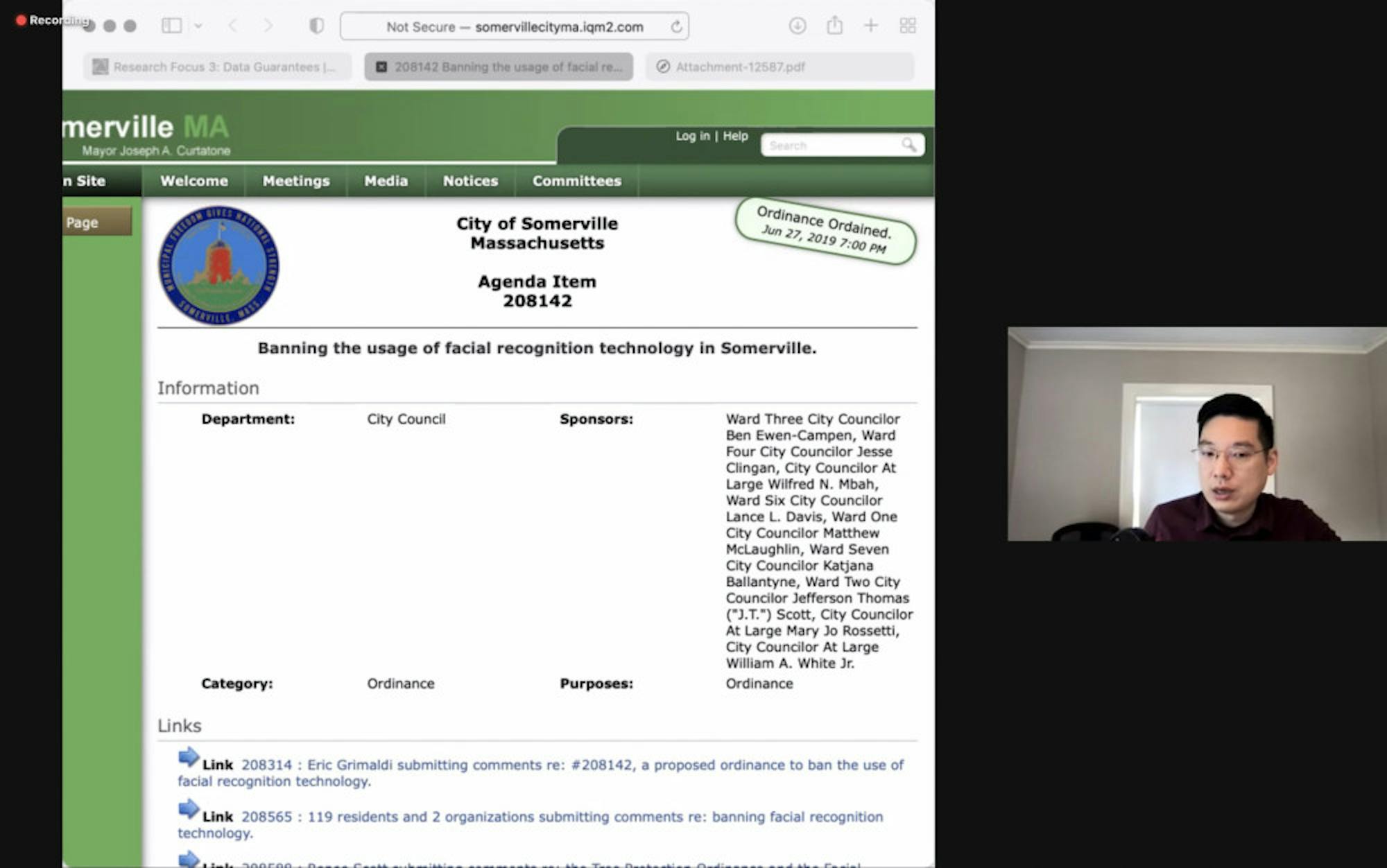

The seminar focused on facial recognition surveillance technology, with featured speakers Ben Ewen-Campen, a current Somerville city councilor and researcher at Harvard Medical School, and Kade Crockford, the director of the Technology for Liberty program at the ACLU of Massachusetts. The two worked together to pass a ban on the use of facial recognition technology in police investigations in Somerville in 2019.

According to Ewen-Campen, the ordinance requires new surveillance technology to go through a public approval process before implementation.

“We have passed what's called a surveillance oversight ordinance which says any new surveillance technology that the [police department] ... want[s] to buy, [these requests] actually have to come before the city council and have a public process, and then get an affirmative vote from the city council to either buy or or start using these technologies," Ewen-Campen said.

Crockford explained how the process occurred without much debate in Somerville, and has since expanded to other communities in the state.

“I think [Ewen-Campen] actually reached out to me because our colleagues in San Francisco passed the nation's first ban on government use of face surveillance. So [Ewen-Campen] was like, 'Hey I want to do this in Somerville,' [and] it was a relatively quick process," Crockford said. "We got it done within six weeks or something, and then that really set off a chain reaction where other municipalities wanted to do the same thing, so we worked with folks in six other municipalities throughout the state to do that."

After the ordinance passed in Somerville, the ACLU of Massachusetts has campaigned to pass municipal bans and educate both the public and local lawmakers about facial recognition surveillance technology and the dangers posed without proper oversight. Crockford further explained the goal to protect communities across the whole state.

“The blunt instrument of a total ban was what we thought was appropriate and necessary for municipal level law … to create the kind of regulations that we think are appropriate,” Crockford said.

Crockford explained the differences between three different forms of surveillance technology.

The first, face surveillance, is defined by Crockford as “the application of video analytics algorithms using biometric identifiers to video data.” This can include examining video data to piece together someone’s movements over a certain period of time.

Crockford explained the danger of face surveillance.

"There's no real way of ensuring accountability and oversight, even if we had the best possible law that said, 'Police can only activate [this] system in limited circumstances,'” Crockford said.

The second technology is emotion analysis, which, according to Crockford, is based on the idea that algorithms can determine what people are feeling based on their physical characteristics. Crockford said that emotion analysis is not a "legitimate science" because it is extremely difficult to interpret emotions based on someone’s facial expression.

"[Someone] might be smiling, but they’re actually extremely nervous — people have that reaction. They might be telling the truth, but fidgeting, because they are anxious because they’re in a police interrogation," Crockford said. "The video analysis system might say, ‘Well, this person is being dishonest,’ when in fact they’re not — they’re just having a normal human response to a stressful situation."

Crockford acknowledged that certain legitimate applications of this technology existed, such as a system that automatically alerts truck drivers if they appear to be falling asleep.

The third form of facial recognition technology is known as image matching. This technology is used when a post or video online shows a crime being committed, after which a police officer can use screen capture to get a clear image of the perpetrator’s face. They then take the image and other evidence to court, and through probable cause, request permission to use facial recognition technology to identify the suspect.

Crockford believes this technology is different from both face surveillance and emotion analysis.

"It poses less of a threat to our basic civil rights and civil liberties because we’re not talking about analyzing all video surveillance data, [only] individual criminal investigations when a human being has identified a still image of a person ... relevant to a criminal investigation,” Crockford said.

According to Crockford, Massachusetts has hundreds of different police departments, meaning that centralizing the process of image matching can prove to be effective in criminal investigations. Crockford proposed that local police should get a warrant to identify a suspect from an image and then take the image to the state police department, which has a facial recognition system.

"We think this is the right solution, because when there's one algorithm that all police departments are using, it's possible for there to be real oversight and accountability to make sure that that algorithm is independently audited [and] has low racial bias rates," Crockford said. "It's possible in that scenario for there to be oversight of police use, because there's only one entity, the Massachusetts State Police, that is responsible for performing all of those searches ... So that is the end game regulatory solution that we're aiming for."