What will live on after your death? According to Hollywood, it won’t just be your children, accomplishments or legacy. In fact, for many of the most acclaimed silver screen performers, the term “death” may be an exaggeration. Technological advancements in CGI and artificial intelligence made during the past 15 years are paving the way for the film industry to keep its actors evergreen, defying death and reversing age. However, many people can’t help but feel like something is off with current implementations of this technology, and evolutionary science agrees.

Although digital makeovers have been done in movies for decades, there has been a recent uptick in complete facial transformations. Brad Pitt’s lead role in “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” (2008) was one of the earliest examples of significant usage of CGI facial reconstruction in film. Pitt’s face was captured with a camera system that was advanced for its time, allowing CGI artists to track his facial expressions and digitize his performance. The team then created realistic 3D models of his face at different ages and superimposed them on his face in the original scenes. “Benjamin Button” paved the way for more advanced CGI: CGI that can only rely on an actor’s natural performance, reducing much of the computational work.

Eight years later, “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” (2016) would use similar technology to recreate the likeness of Peter Cushing and a young Carrie Fisher. However, neither Cushing nor Fisher appeared in the film in any capacity — namely due to Cushing’s death nearly 22 years prior to the film. Instead, their performances were done by lookalikes wearing facial capturing equipment, and their faces were recreated by CGI artists who tried to replicate the actors as closely as possible.

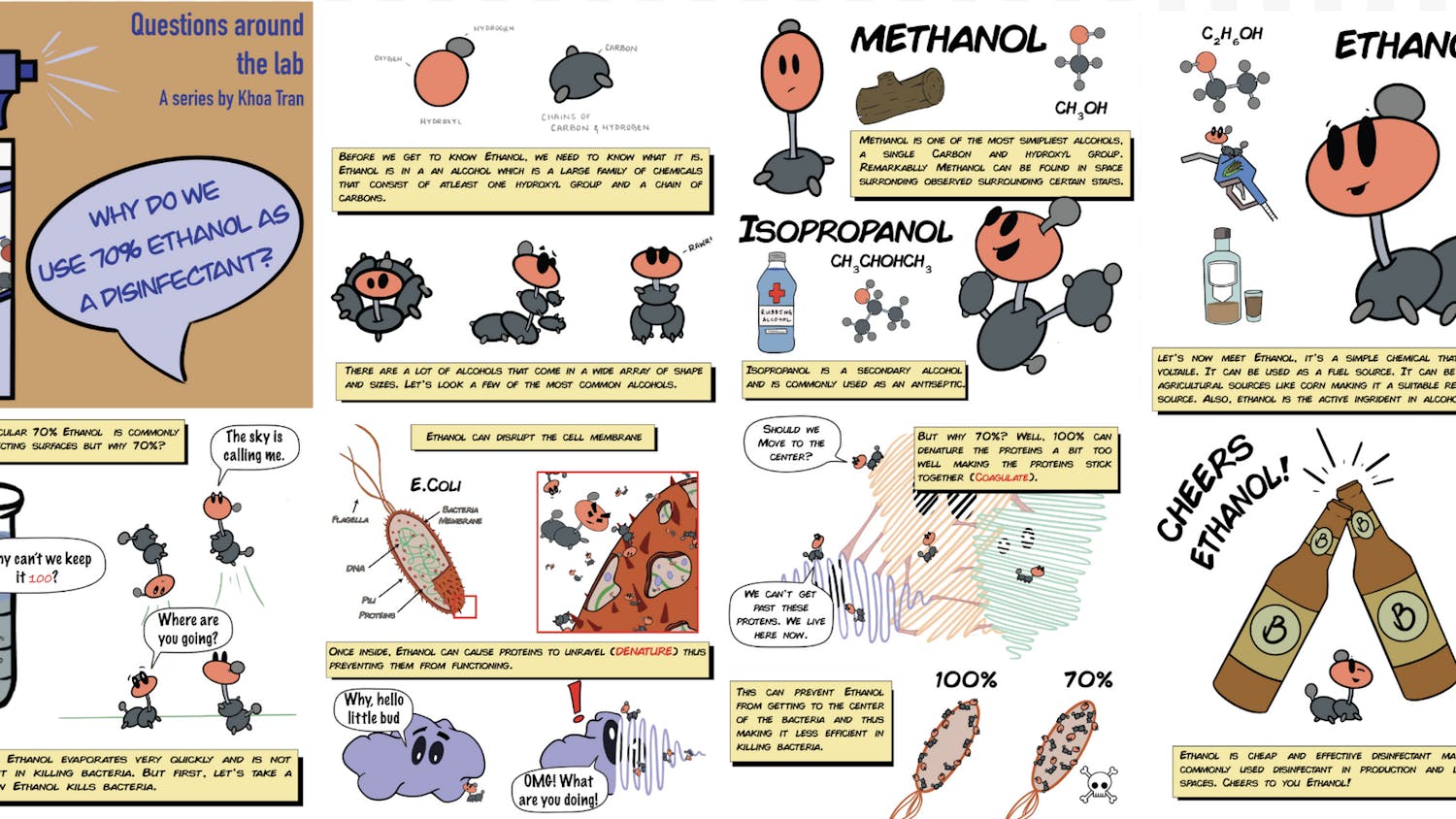

Recreating an actor’s performance without the actor present is likely to explode in popularity thanks to the rising practice of “deepfaking,” a method of creating images and videos using AI. Like traditional motion capture, real human performance is used as the base for the final product. The key difference is that CGI methods require hours of work by artists to digitally restore an actor. In contrast, deepfaking uses AI that can teach itself how to reconstruct and superimpose a face onto another based on recordings of an actor’s past performances. Most importantly, creating deepfaked media only requires a standard computer and a face reasonably similar to the target. The results are incredibly convincing compared to CGI and can almost escape the uncanny valley. Putting aside glaring ethical questions, you might wonder whether the results are worth the effort. It would seem that no matter how far the technology improves, many people still find the end product uneasy to watch. Most often this phenomenon is referred to as the uncanny valley effect. When something verifiably not human, like a CGI face, bears too close a resemblance to a human, it is said to lie within the uncanny valley.

Many studies have attempted to expand scientific research on the uncanny valley to identify a particular root cause in human psychology. A paper published this month in Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans set out to identify how various individual elements of a person’s psyche could play into the effect. Throughout two separate studies, researchers found that they could predict the types of images that participants found uncanny based on several variables such as a person’s coulrophobia (that’s fear of clowns) or anxiety. The study found that the uncanny valley effect produced by CGI faces was most directly linked to an individual’s sensitivity to disgust. Humans have evolved to be highly adept at recognizing faces, so the small imperfections often present in digitally recreated faces likely get amplified by the brain, which then associates the abnormality with malady. As a result, it's speculated that the unease one feels upon looking at something uncanny is the brain sounding the alarm on a potentially dangerous encounter. So, the next time your stomach knots at Hollywood’s latest digital resurrection, you can thank evolution for looking out for you.