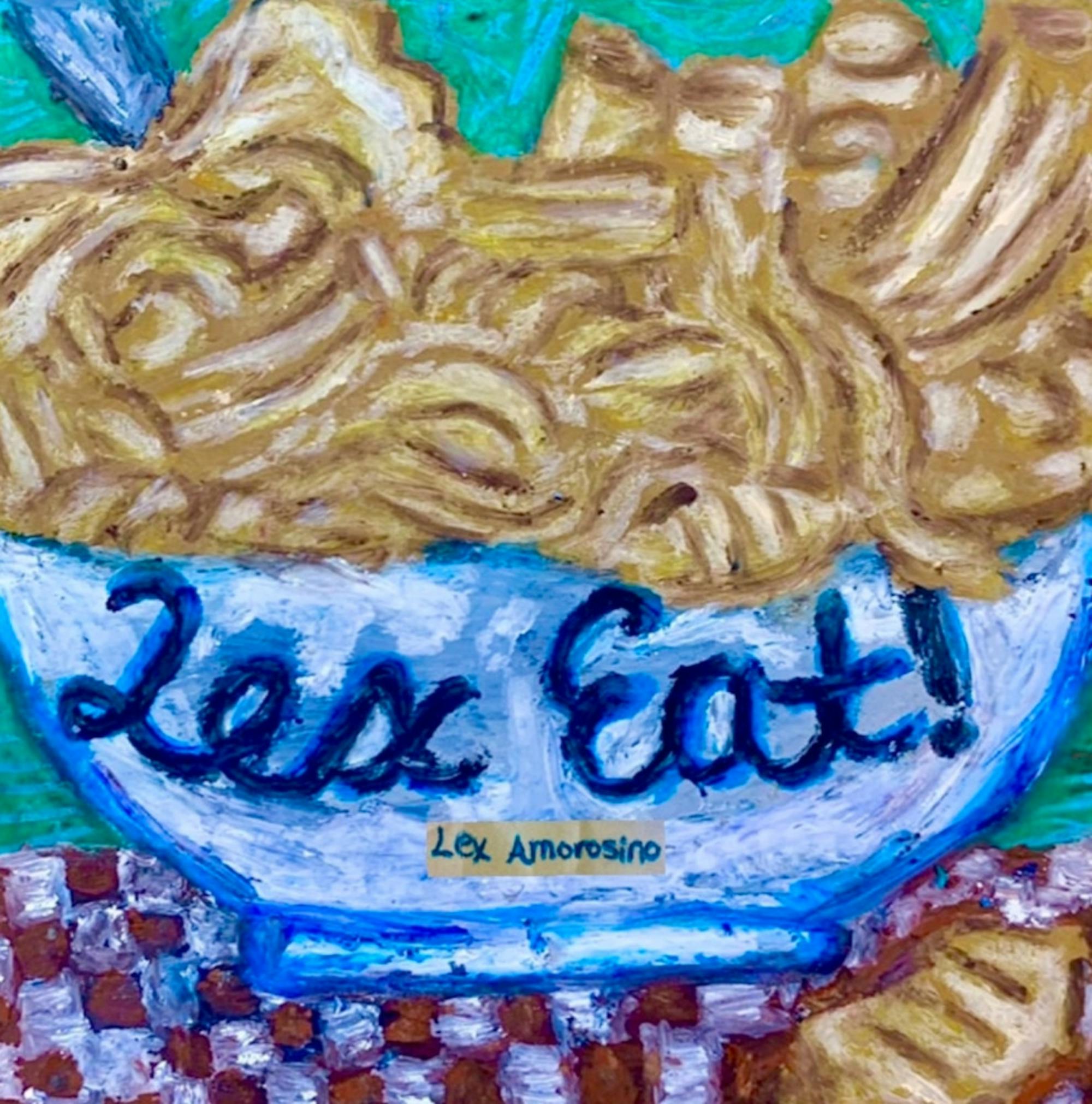

I can’t write a food column in Italy without giving pasta its moment — so let's talk about it.

Pasta is truly all-encompassing in terms of what it represents in Italian culture.

Traditional pasta making is a fundamental part of the Italian experience, and customarily, a family affair. Italian grandmothers spend hours kneading dough, rolling it out and shaping it, surrounded by wide-eyed grandchildren who will pass down these recipes and techniques to future generations.

A simple recipe made from ingredients that are cheap and plentiful around Italy, peasants have long turned to pasta for sustenance in the face of scarcity. Its humble origins make this staple a symbol of resourcefulness.

With hundreds of variations in shape and specialties in each region, pasta pays homage to the diversity within Italy. Its versatility makes it the perfect vessel for so many extraordinary fillings and sauces. While preparations vary, pasta can be found all over Italy, and — as an ingredient — it unifies the country across its different cuisines.

Over the past two months, I’ve eaten my fair share of pasta dishes — each with its own flair and unlike anything I’ve had in the United States. An authentic Italian pasta dish is surprisingly light. The key? Fresh, and certainly unprocessed, pasta made from special Italian flours. While the sauces are delicious, it's the chewy texture and bright flavor of the pasta itself that makes these dishes exceptional.

To learn more about the ritual of pasta making, I took two cooking classes: one in a professional kitchen with a Sicilian chef and one in a family home with a Milanese grandma named Bruna.

The chef taught me how to make pasta with Semolina flour and warm water. Semolina flour is made from the hardest species of wheat, Durum wheat, which possesses a unique stretchability. We simply combined the ingredients in a bowl and kneaded the dough until it was bouncy. Now comes the tricky part: We made two shapes of pasta: “gnocchetti”and “trofie.” The process was time consuming and required a dexterity that clearly takes years to perfect.

Next, my class with Bruna — and boy was this little lady a character. In the midst of all of her stories, she showed us how to make fresh egg pasta. This time we used a mound of soft wheat that had been ground into a powder, made a well in the center and added freshly cracked eggs. Again, we earnestly kneaded that dough and let it rest. Then, we used a machine to roll the dough into thin sheets. Half was cut into thin strips, and the other half was carefully layered with an insane “cacio e pepe” ricotta and cut into fun shapes. The result: the silkiest “tagliatelle” and perfectly delicate “ravioli.”

In both instances, I was surprised how simple it was to make the dough and how complicated it was to shape the pasta. While my two experiences were very different, the focus on quality ingredients and the aspects of longstanding tradition, passion and pride were consistent.