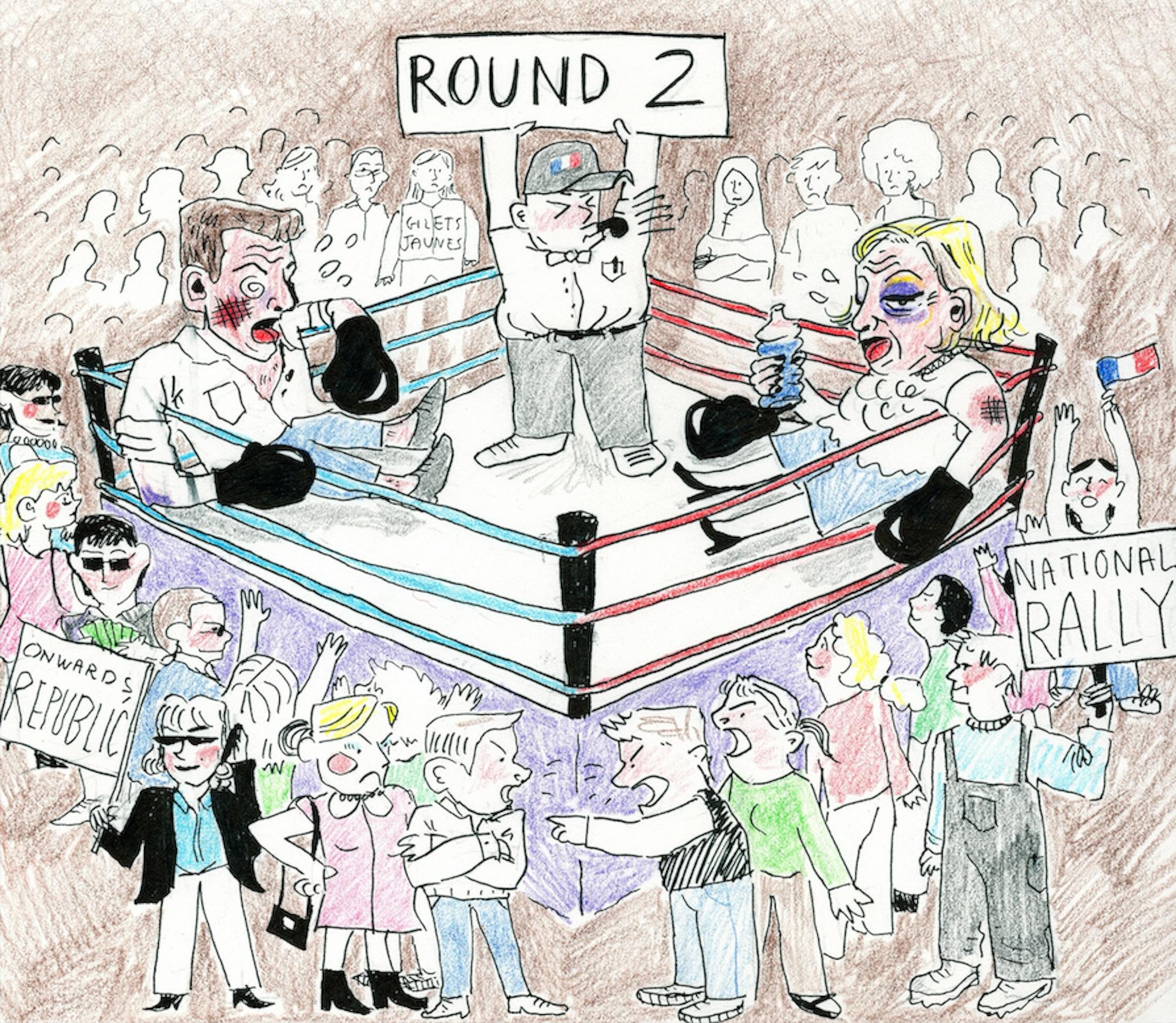

The first round of the French presidential elections came straight from a textbook. Held on April 10, the elections sent current President Emmanuel Macron, head of the centrist political party La République En Marche! (“The Republic On The Move” in English), to the second round with an admirable 27.85% of the vote.

Pundits and pollsters alike have long given incumbent Emmanuel Macron a big lead in the polls, which pushed the president to declare his candidacy late and campaign very little. This strategy backfired, as some voters may have viewed this move as contempt for his competition and general pretension. His ratings progressively tanked, placing him within reach of the far-right perennial Marine Le Pen.

Le Pen had initially suffered from TV pundit-turned politician Éric Zemmour’s campaign. Zemmour positioned himself as a rival of Le Pen, taunting the French public with similar populist and bigoted antics to those of former President Donald Trump. At one point, Zemmour was neck and neck with Le Pen in the polls, and there were fears on the far right that the electorate was cannibalizing itself. But this allowed Le Pen to clean up her candidacy. Dropping many of her anti-EU slogans, she started advocating for popular social causes, such as lowering the retirement age and putting a heavy accent on restoring the French’s purchasing power. She won over some of the traditional moderate right and even some of the left’s electorate. The latter demographic is disenchanted by the progressively weaker Parti Socialiste (Socialist Party) and the poor showing of their candidate, Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, who is deeply unpopular outside her city. This gear shift propelled Le Pen to late campaign gains that led her to collect 23% of the vote, leaving Zemmour far behind at around 7%.

The traditional French parties now face an existential threat. The Socialist Party only got 1.75% of the vote, down from 6.36% in 2017. As for their traditional opposition, Les Républicains (The Republicans), the result might be even more catastrophic given the magnitude of their fall: They failed to get more than 5% of the vote. This result is a big deal because, under French law, a party is only entitled to subsidies or refunds for their costly campaigns if they reach that threshold, forcing candidate Valérie Pécresse to borrow 5 million euros under her own name to maintain the party afloat and seriously hurting their electoral machine ahead of crucial parliamentary elections in June.Indeed, The Republicans currently have more than 100 members in Parliament and will need to fight hard to maintain this group, which is already less than half the number that Macron’s party holds.

Most candidates have already called to vote for Macron in the second round to block the far right from reaching the presidency. Third-place Jean-Luc Mélenchon exhorted his supporters not to give Le Pen a single vote, while Valérie Pécresse, Anne Hidalgo and Yannick Jadot all directly endorsed the current president. This highlights the real fear amongst the political establishment that Le Pen has her first true chance of success. Zemmour’s endorsement angles his voters toward her, setting her up to win 30% of the vote. But is France ripe for far-right populism? In all likelihood, not yet. A sizable chunk of the population still sees a right-wing vote as taboo and will likely choose to vote for Macron just to block Le Pen. Furthermore, the French generally support E.U. membership, and Le Pen’s pivot to more moderation toward Brussels is still too recent to be seen as genuine. There isn’t grassroots appeal for a euroskeptic populist, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which placed Le Pen in an awkward position, as she had been a vocal admirer of Vladimir Putin. Thus, we can foresee that Macron and his “The Republic On The Move” party may face a more formidable challenge in parliamentary elections.

Traditionally, parliamentary elections are held right after presidential elections, ensuring a majority and allowing the president to govern for his five-year term. However, unpopular measures brought forward by Macron have led some to denounce the rubber-stamp nature of the National Assembly. While Marine Le Pen showed in 2017 that a strong showing does not guarantee legislative success (her party only won 8 seats in the 577 seat assembly), Mélenchon could quickly turn into a kingmaker in Parliament. His party currently only holds 17 seats, but he has turned into a much more palatable and legitimate political figure since the 2017 contest. His “La France Insoumise” (“France Unbowed”) party is consistently popular with the youth, which offers him an overwhelming dominance on social media platforms and campuses. In my view, they will make strides in the upcoming elections, especially considering the beating taken by both The Republicans and the Socialist Party and Marine Le Pen’s still repugnant image with many of the French. Macron can count on the consistency of the Democratic Movement Party, which has ruled in coalition and offered him a sturdy supermajority in Parliament. But it is The Republic Marches On! that is most at risk of losing seats. They had a dismal showing in the municipal election last year, winning barely 12.46% of the vote, essentially through coalition partners. The party benefited from the scandals that hit The Republican’s candidate in 2017, along with François Hollande’s unpopularity that badly tarnished the Socialist Party’s appeal. Today, Macron has to immediately start leading an aggressive campaign in stark contrast to his presidential run. Macron should expect political blockage and tough negotiations if he doesn’t win a majority. And with his ambitious agenda of economic and international diplomatic investment, Macron cannot afford to make many concessions. Mélenchon’s base has already shifted their sight to June, seeing the parliamentary elections as both a referendum on and a message for Emmanuel Macron: ‘We elected you because we had no choice, but you don’t get carte blanche this time.’

That being said, I still believe Macron benefits from a discrete and determined majority amongst the urban French and the upper-middle class. He has vowed to place France back on the map, and while his economic policies hurt the worker, they please a significant portion of the population that wants to see France lifted from its economic stagnation. I believe renewing his supermajority might be a tall order, but the first round has shown Macron will likely rule for five more years and continue to try to impose his reformatory agenda, albeit against a backdrop of increasingly hostile and partisan opposition.