Amid the near-total Israeli blockade, those in Gaza are facing a new threat to their lives — paralytic diseases. According to Nasser Hospital’s head of pediatrics, Dr. Ahmed Al-Farra, “Before the war, we used to see one case of Guillain-Barré syndrome yearly, but in the last three months, we have already diagnosed nearly 100 cases. We are seeing an outbreak of acute flaccid paralysis as a result … Patients are fatigued, unable to stand or sit. Then, as the paralysis increases, it affects patients’ respiratory muscles and can lead to respiratory failure. This can, in some cases, result in cardiac arrest.”

Guillain-Barré syndrome is a rare neurological condition in which the body’s immune system attacks peripheral nerves, impairing the myelin sheath or nerve axons, which carry signals between the brain, spinal cord and limbs. Initial symptoms usually present as random, unexplained sensations, like tingling in the hands and feet. These symptoms can then progress to tingling in the legs and back, then to difficulty ambulating. In severe cases, the syndrome can lead to total paralysis.

The American Brain Foundation states, “Other symptoms can include issues with eye movement and vision, difficulty swallowing or speaking, coordination problems, abnormal heart rate or blood pressure, and digestive or bladder control problems.”

The timeline of this syndrome’s progression can vary, with symptoms usually developing over days to weeks. In most cases, patients are at their weakest two to three weeks after the initial onset of symptoms, but full recovery often takes several months or more; some patients are left with lasting weakness or disability.

So what’s driving the surge in cases in Gaza? Multiple overlapping factors appear to be contributing to the outbreak, namely poor WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) conditions, as well as malnutrition. With airstrikes having destroyed water and sanitation networks, Gazans are left with no choice but to use wastewater for drinking, cooking and washing. Further, lack of reliable food and nutrition weakens immune defenses, making severe infections — which can trigger the syndrome — more likely. “Given the water sanitation and health situation … the conditions are ripe for any infection,” World Health Organization spokesperson Christian Lindmeier said.

Guillain-Barré has a history of surfacing in wartime settings, underscoring the relationship between armed conflict, the consequential degradation of living conditions and the emergence of acute paralytic illnesses. The first well-documented description of what we now call Guillain-Barré syndrome occurred during World War I in 1916, when French neurologists Georges Guillain and Jean-Alexandre Barré, as well as physiologist André Strohl, described two soldiers in the French Sixth Army who developed acute progressive motor weakness, loss of tendon reflexes and elevated cerebrospinal fluid protein despite a normal cell count. Reports of similar cases, often referred to earlier as Landry’s paralysis, had existed since the 19th century, but it was the context of war that crystallized the syndrome as a distinct neurological disorder.

During World War II, American and British military physicians documented numerous cases of acute paralytic neuropathy, many of which were later recognized as Guillain-Barré syndrome, with several fatal cases underscoring its severity. These historical contexts suggest that the combined stresses of war, including malnutrition, crowded living conditions and poor sanitation, consistently create fertile ground for Guillain-Barré syndrome outbreaks.

Today, the reappearance of the syndrome in Gaza serves as yet another reminder that such outbreaks are not incidental but a direct consequence of war’s devastation, where medical vulnerability is amplified by the very conditions of conflict, and the burden falls most heavily on already suffering civilian populations.

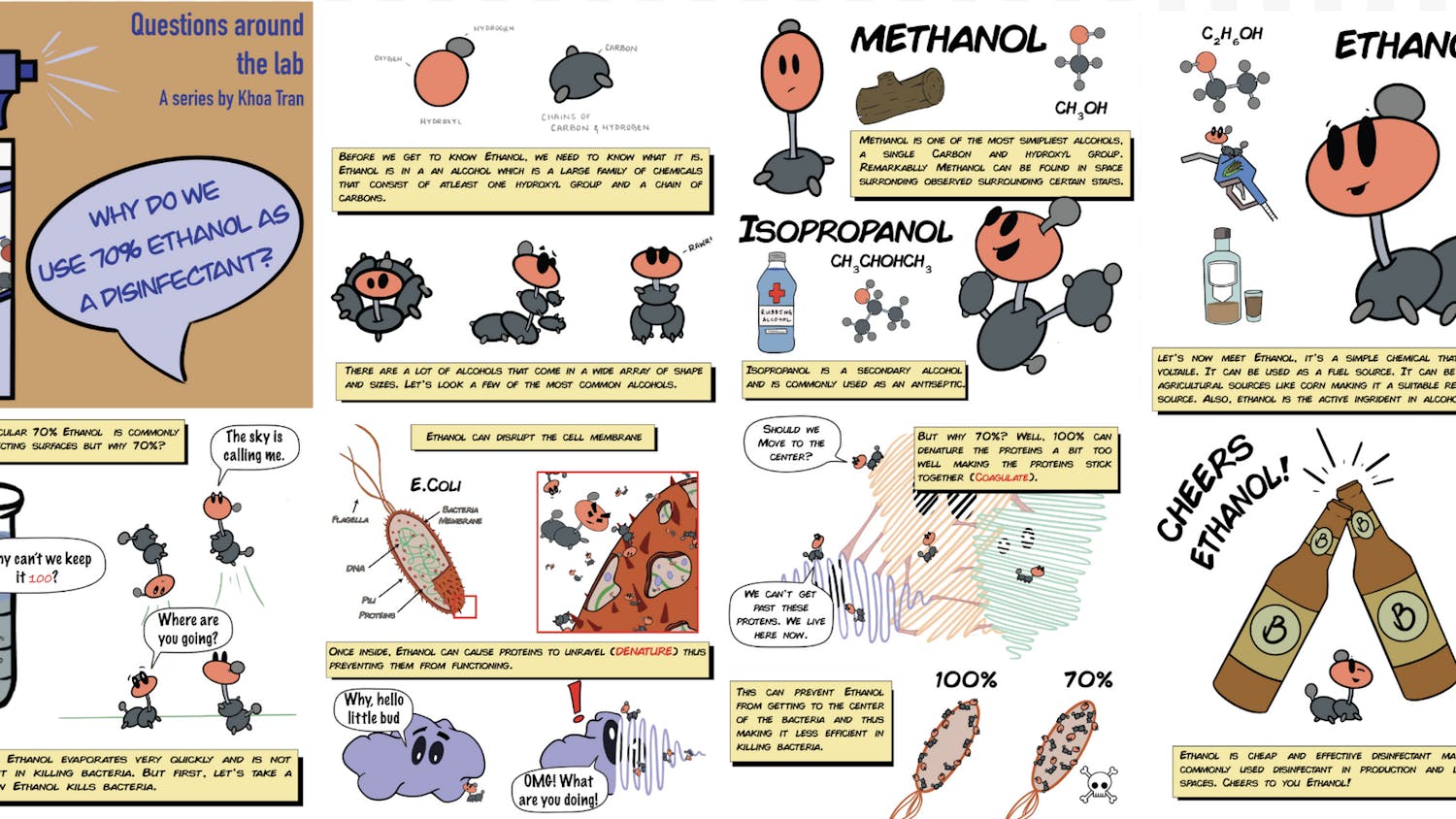

Due to its complex, poorly understood triggers, Guillain-Barré syndrome has no simple cure. The immune system mistakenly attacks peripheral nerves, but the exact cause, timing and severity differ widely across patients. As a result, no universal ‘fix’ exists; however, established therapies can dramatically reduce severity and improve recovery. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment works by infusing concentrated antibodies into the affected patient’s bloodstream. Plasmapheresis, another treatment for the syndrome, filters out immune molecules responsible for symptoms by circulating the patient’s blood in a machine that exchanges the plasma for a substitute solution. These treatments are most effective when started early. They reduce the risk of severe paralysis and respiratory failure, shorten hospital stays and lower mortality rates.

In Gaza, however, treatments are largely unavailable or severely limited. “Intravenous immunoglobulin … the (Gaza) Ministry of Health’s first-line treatment for GBS, and plasmapheresis filters remain out of stock, leaving no treatment options available for suspected GBS cases,” the WHO said.

Waleed Ghalibeh’s story mirrors the plight of other patients in Gaza, showing how a sudden onset of Guillain-Barré syndrome can devastate families already enduring immense hardship. Ghalibeh’s condition began with a sudden onset of symptoms, including the loss of his ability to speak and swallow, followed by difficulty blinking. Despite receiving intensive care for 17 days, he remains unable to speak, eat or breathe independently, relying on a feeding tube and mechanical ventilation. His mother expressed a deep desire for him to regain his previous abilities once more.

“The thing that I wish for the most, and I truly want to see it in front of my eyes, is for my son [to] talk, breathe, eat, drink, love life, pray and walk on his feet like before. This is what I really wish for the most, for me to see him healthy like before,” she said.

The surge of Guillain-Barré syndrome in Gaza is not simply the appearance of a rare neurological illness but the predictable consequence of collapsing public health foundations. The destruction of WASH infrastructure forces families to consume unsafe water, while overcrowded shelters heighten the spread of infectious diseases.

Malnutrition and compromised immunity leave individuals less able to fight even routine illnesses, turning otherwise manageable infections into life-threatening conditions. At the same time, restricted access to healthcare, shortages of essential treatments and limited diagnostic capacity mean that patients like Ghalibeh are left without lifesaving treatments. His story reveals how quickly a fragile health system can unravel when these risk factors converge. Ultimately, the surge of Guillain-Barré in Gaza demonstrates how war dismantles the foundations of a healthcare system, transforming preventable illnesses into crises and leaving entire populations vulnerable to the compounding toll of conflict.