Each year, six Nobel Prizes are awarded in the fields of physiology or medicine, physics, chemistry, economics, literature and peace work. This year, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Shimon Sakaguchi for their groundbreaking discoveries in peripheral immune tolerance — the mechanism by which the immune system prevents itself from attacking the body’s own cells.

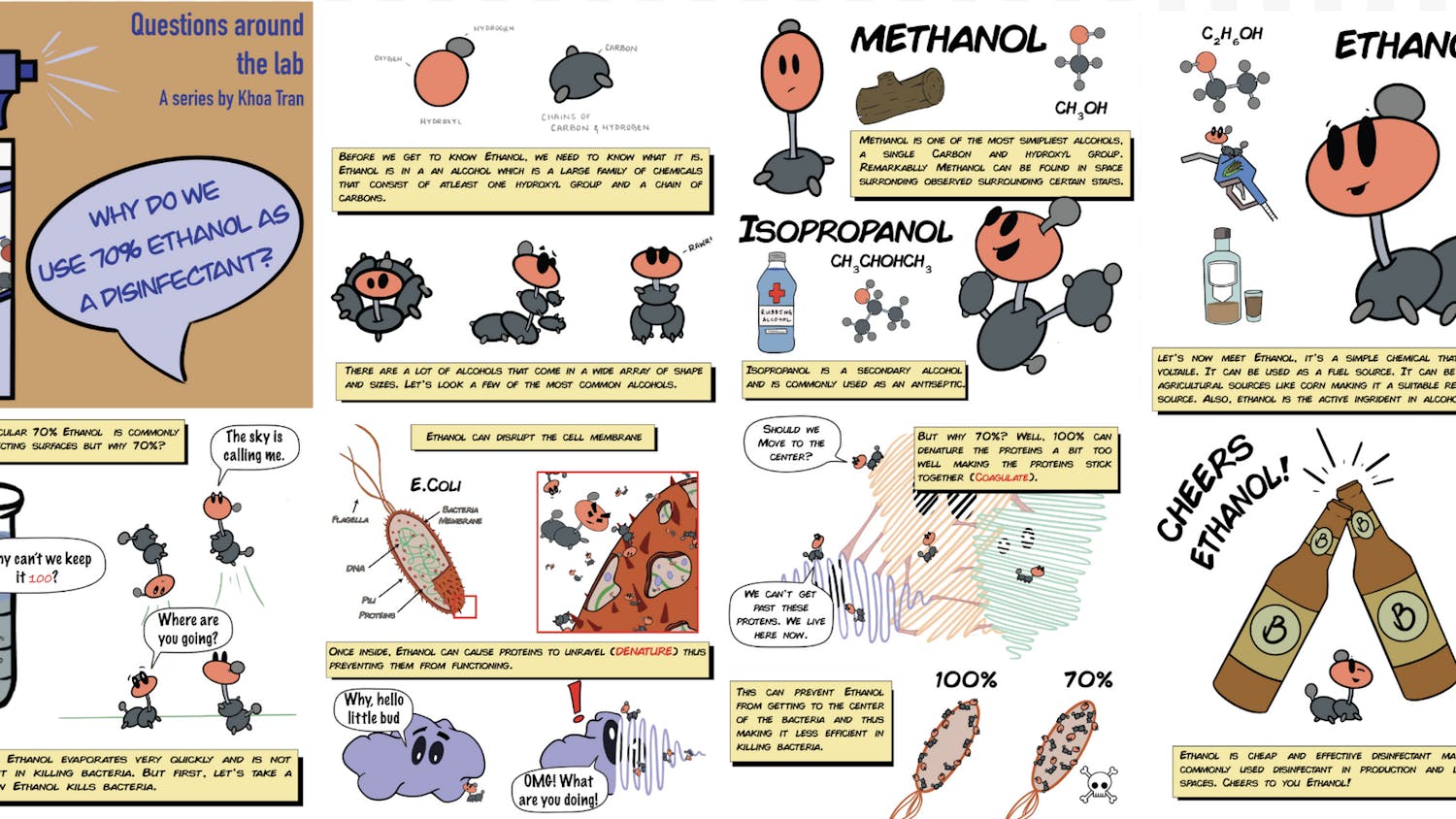

The immune system plays a crucial role in defending the body against bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. Central to this defense are T cells, which are responsible for identifying and eliminating foreign invaders. T cells specifically are designed to remove a certain kind of threat and can copy themselves to eliminate an intruder. However, it was long unknown how the immune system manages to avoid autoimmunity, or the attacking of its own tissues.

In 1969, while researching at the Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute in Nagoya, Japan, Yasuaki Nishizuka and Teruyo Sakakura made a pivotal discovery that brought modern science a step closer to solving the mystery. When they removed the thymuses (immune cell training centers) of newborn female mice, they found their ovaries were attacked by their own immune system as their bodies spontaneously promoted autoimmune-like diseases. However, when these thymus-free mice were inoculated with normal T cells, the disease was inhibited. This suggested that there were types of T cells that prevent or suppress disease development.

In 1995, Sakaguchi built off of Nishizuka and Sakakura’s work to make groundbreaking discoveries, revealing the existence of a previously unknown class of T cells, now known as regulatory T cells (T-regs). T-regs suppress excessive immune responses and prevent autoimmunity by impeding cell multiplication and reducing secretion of cytokines — chemical signals that facilitate cell-to-cell communication. By controlling the activity of other immune cells and preventing unnecessary or harmful attacks, T-regs act as the ‘peacekeepers of the immune system,’ preventing damage to the body it is meant to protect.

Following this discovery, in 2001, Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell identified a critical genetic factor behind this regulatory mechanism: FOXP3, a key molecule in controlling the development and function of T-regs. FOXP3 is a transcription factor that tells genes on and off, regulating and inducing gene activity in developing T-cells, causing them to develop into T-regs. A mouse with a mutation that makes FOXP3 inactive develops massive inflammation in many organs, leading to early death.

Mutations in FOXP3 lead to a rare autoimmune disorder known as immune dysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy, X-linked syndrome. This genetic defect occurs on the X chromosome and disrupts FOXP3 production, preventing T-regs from developing properly, limiting their roles in both fighting and facilitating viral infections — including HIV — and in maintaining peripheral tolerance.

Sakaguchi’s earlier work helped confirm that the FOXP3 gene is essential for T-reg formation and function. Together, these discoveries profoundly advanced our understanding of immune regulation. They not only explain how the body maintains tolerance to its own cells but also open new avenues for medical treatment.

Insights into FOXP3 and regulatory T cells now guide the development of therapies aimed at controlling immune responses — whether by suppressing autoimmunity or enhancing the immune system’s ability to target cancer cells. Currently, this discovery has inspired over 200 clinical trials exploring therapies to treat autoimmune transplants, improve organ transplants and potentially treat cancer.

To be more specific, this research has led to current clinical trials working towards the development of treatments for autoimmune diseases, including trials aimed at treating lupus erythematosus, inflammatory myositis and systemic sclerosis. Many of these trials involve the use of chimeric antigen receptor T-cells, which genetically engineer a patient’s T-cells to express the CAR protein — allowing them to target cells that drive disease.