It’s easy to view climate change and environmental issues at large as being inherently partisan. Recent polling shows stark differences in how Republicans feel about climate change versus Democrats. Not a single Republican voted for former President Joe Biden’s environment-centric Inflation Reduction Act. Additionally, our current Republican president has officially left the Paris Climate Agreement. However, in spite of the seemingly intrinsic nature of today’s partisan environmental disagreements, caring for our world was once an issue that brought the U.S. government together.

While there were American environmental policies in the pre-Nixon era — like the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 or the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955 — it wasn’t until the Nixon administration that protecting the environment became a priority. Former President Richard Nixon founded the Environmental Protection Agency, signed the Clean Air Act into law and allowed the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act. In many ways, he established the foundation for environmental policy in the U.S., and many of the laws he signed into place continue to play a critical role.

Nixon is an important example because he refutes many of the justifications as to why environmental policy became so partisan. It has been argued that because Republicans align themselves with the free market and deregulation, they will inevitably be ideologically opposed to environmental regulatory policy. However, this is disproven by Nixon spearheading environmental policy in the U.S. Even former President Ronald Reagan, who was notoriously anti-regulation, supported the Montreal Protocol, a treaty designed to limit the production of ozone-depleting chemicals. In fact, U.S. public opinion data shows us that this was the time when both Republicans and Democrats were the most united on environmental policy, even as Reagan’s conservative policies gained traction across the U.S.

Once we understand that Republicanism is not inherently anti-environment, the question then becomes: How did environmental policy become so polarized? This is a question that has been asked and answered a slew of times, but there are a few very apparent factors. That same U.S. public opinion data also shows us that throughout the 1990s, Republicans suddenly became increasingly anti-environment, with Democrats remaining largely stagnant in their beliefs.

While it is impossible to pinpoint any one specific cause for this shift, it is important to note that this shift took place at the same time that the Global Climate Coalition was at its height. Formed just two years earlier, the GCC was made up of U.S. businesses and industries aiming to sway environmental legislation. Such members included General Motors, Chrysler Corporation and Shell Oil Company. Coalitions such as these worked to spread disinformation surrounding climate change, sowing doubt in the minds of Americans as to the validity of scientific findings. At the same time, it directly impacted legislative decisions, swaying the Clinton administration to enact voluntary instead of mandatory emissions reductions on corporations and even influencing the 2025 UN Climate Change Conference in Rio de Janeiro to agree on weaker legislation.

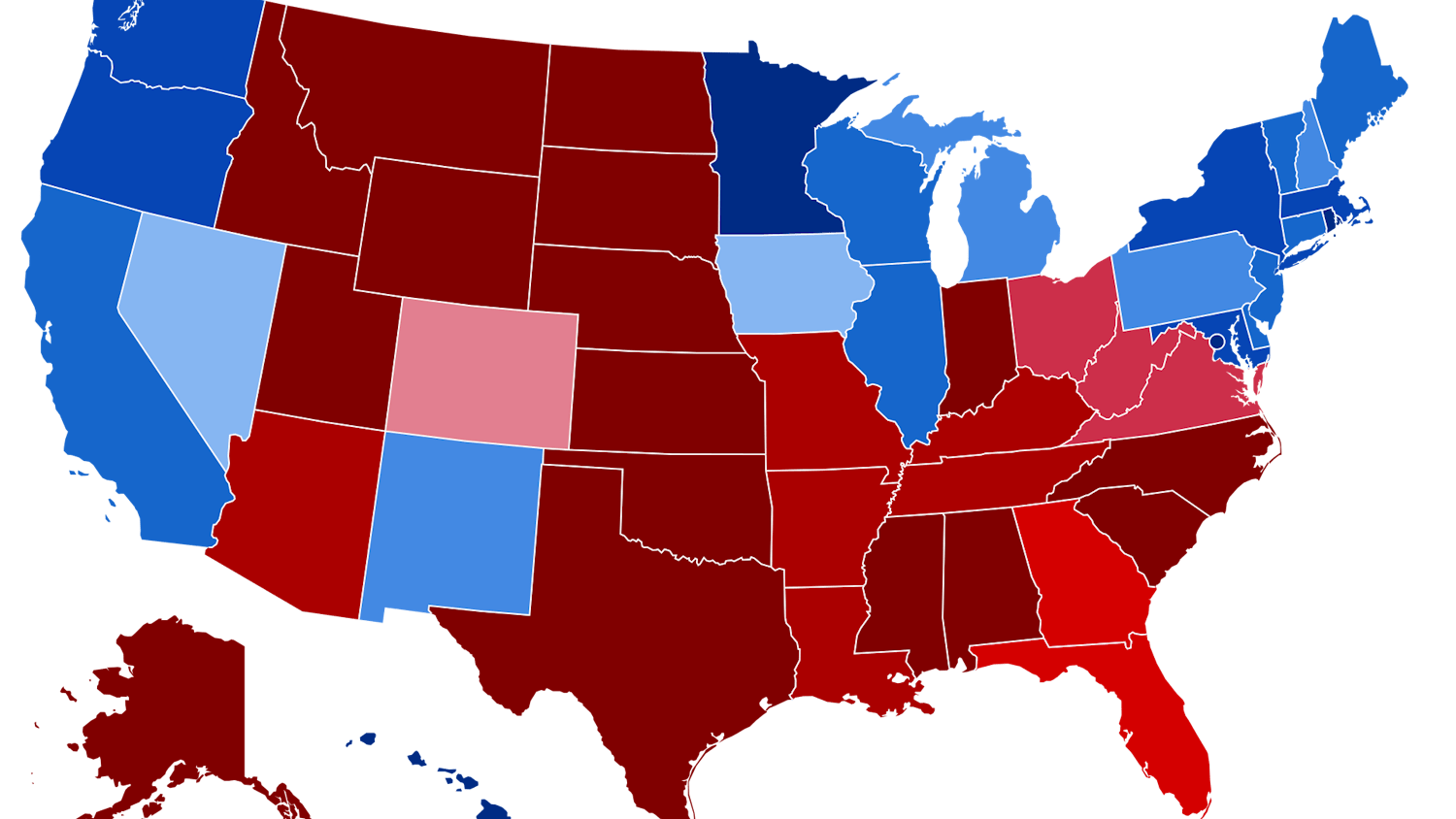

Being made up of such wealthy corporations, the GCC was a powerful lobby. Within their lobbying decisions, we begin to see a potential explanation for the radical partisan shift in environmental policy. When the GCC first started gaining traction in the early ’90s, it lobbied more towards Republicans at a ratio of 1.8-to-1. By 2020, that ratio rose to 5-to-1. We can see similar phenomena across various industries which would be economically harmed by fossil fuel reductions, including oil and coal companies. There are a multitude of explanations for why lobby groups like the GCC would favor Republicans — being pro-business, representing more states with oil — but at the end of the day, these groups were able to sway Republican leaders and conservative think tanks via their donations.

That’s not to say that Democrats are completely immune to this kind of influence. Former Democratic Senator Joe Manchin notoriously opposed the proposed Build Back Better Act, effectively blocking its adoption and forcing legislators to instead accept his revised Inflation Reduction Act, which included provisions favoring fossil fuel companies. He also happened to receive close to $1 million from lobbying groups, and even has ties to a coal company himself. Figures like Manchin, who should in theory be aligned with environmental policy, show that money speaks louder than ideology. Even though the GCC has been dissolved for the past few decades, the impacts of it and similar lobby groups still reverberate. Oil and gas corporations continue to spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year on lobbying, and the partisan divide seems to be getting wider and wider.

But we are not helpless in this fight. In spite of President Donald Trump’s many attempts, the green energy sector of the market continues to flourish, and millions of Americans have been gathering together to protest Trump’s harmful policies, including his environmental ones. Tufts students have the power, both now and in our future careers, to take stances in one way or another that better our planet. The future depends on it.