The clinical approval of penicillin in 1945 kicked off a 25-year period that is now commonly referred to as ‘the golden age of antibiotic discovery,’ in which antibiotic discovery progressed at a dizzying pace. In the nearly 80 years since antibiotics emerged on the scene enmasse, their usage has ballooned. Now antibiotics can be found in a plethora of industries, from human medicine to agriculture to livestock.

Antibiotics revolutionized medicine — their discovery cut deaths from infections, lowered maternal mortality and made chemotherapy and organ transplants more widespread. However, the immense benefits provided by antibiotics are threatened by a phenomenon known as antimicrobial resistance. When an antibiotic is used to treat an infection, it will not always be 100% effective. If there is even one cell that has a mutation that provides resistance, that one cell can then multiply and grow, spreading its resistant DNA as it replicates. Decades of widespread antibiotic usage have given rise to many of these resistant bacteria that continue to spread and threaten the efficacy of antibiotics in a wide variety of situations.

Antimicrobial resistance in Neno

The phenomenon of antimicrobial resistance is not equally distributed across the globe. Low- and middle-income countries are disproportionately feeling the effects of this crisis. Among these hard-hit areas is Malawi, a small country located in the southeast of Africa, bordering Mozambique, Zambia and Tanzania. I spoke with Dr. George Limwado, a physician in Neno District, Malawi, to better understand the drivers, effects and research surrounding antibiotic resistance in the region.

Neno District is a rural area in southern Malawi with a predominantly agricultural economy, primarily based on subsistence farming. Limwado works with Abwenzi Pa Za Umoyo, the Malawi branch of the larger international Partners in Health. In that role he both practices medicine in the Neno District Hospital and conducts research with PIH.

Limwado explained that there are a variety of factors contributing to the spread of antimicrobial resistance in Neno. First, awareness of antimicrobial resistance, both of its causes and consequences, is low throughout the district, and this contributes to ongoing engagement in behaviors that perpetuate the issue of resistance.

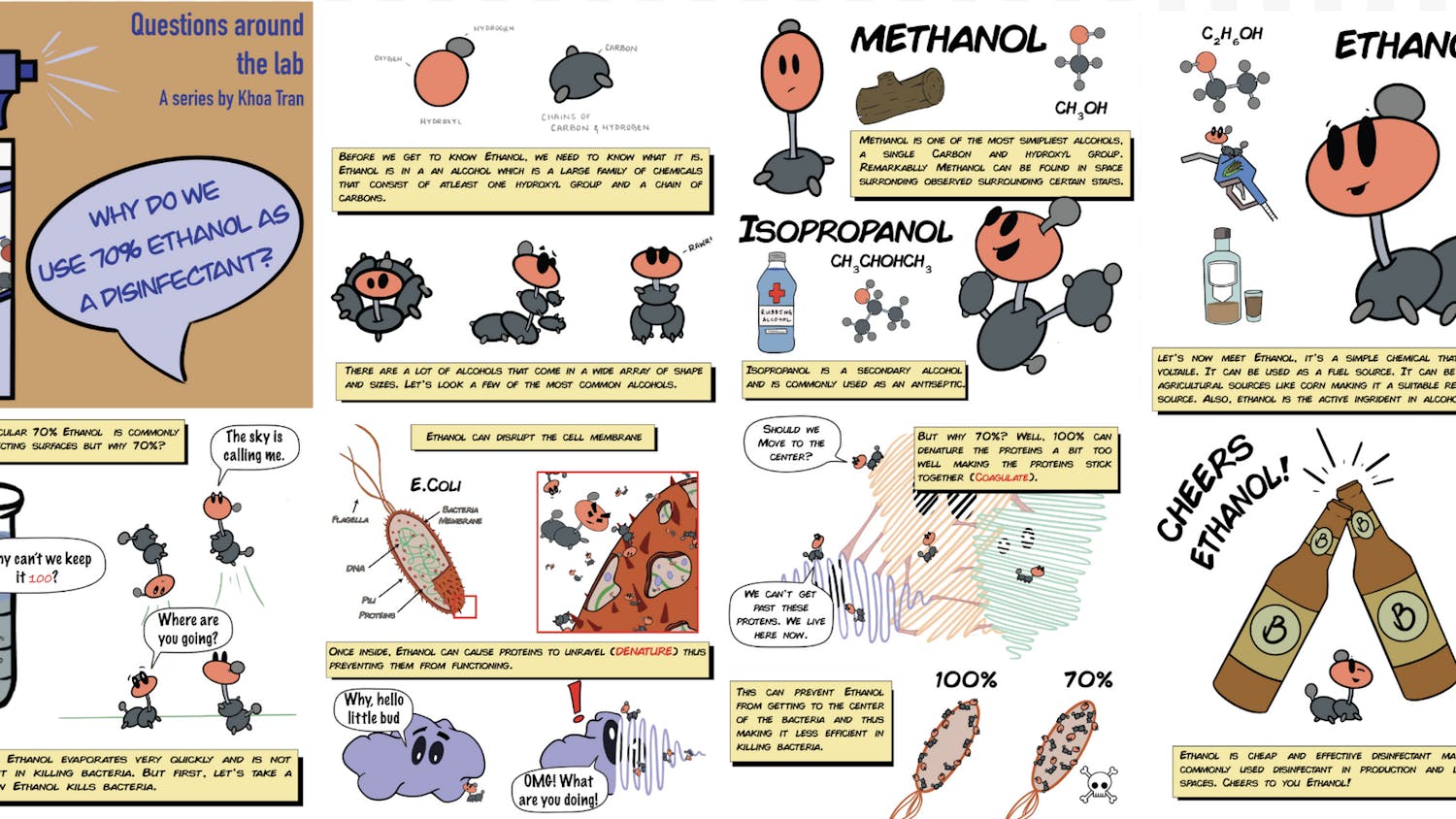

Second, the lack of diagnostics contributes to antimicrobial resistance proliferation because many patients with viral infections are given antibiotics due to the lack of access to the appropriate diagnostics. One example of this is respiratory syncytial virus, an upper-respiratory tract infection that commonly presents with cough and shortness of breath. The issue with RSV is that it presents with similar symptoms to bacterial pneumonia. However, given the lack of RSV rapid test availability at the health facilities, many physicians just prescribe antibiotics for all upper respiratory tract infections due to difficulty in differentiating between viral and bacterial respiratory infections from clinical observations alone. Antibiotics cannot treat an RSV infection but they do provide the microbiota within our bodies more opportunities to develop resistance.

Third, antibiotics continue to be used as growth promoters for livestock in Neno. “There has not been much collaboration between departments, [specifically] the human health department and the agriculture sector … who’s antibiotics in particular, are still being used as growth promoters in farms, which is also an action that contributes to antimicrobial resistance” Limwado noted.

Finally, antibiotic self-medication is a huge driver of antimicrobial resistance in Neno, and last year, Limwado co-authored a study that assessed the extent of antibiotic self-medication and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance in the district. In this study, researchers interviewed more than 500 people and asked them two questions: Have you been self-medicated in the past six months? And, are you aware of antimicrobial resistance?

Limwado found that 69.5% of people interviewed had self-medicated in the previous six months. “The striking thing,” Limwado said, “was that they had gotten these antibiotics from a [health] facility, but they decided to keep some so if they were given maybe a dose for five days, they would only take for two or three days [and] once they feel better, they could keep the other medications and use it later to self medicate.”

After Limwado had explained the root causes of antimicrobial resistance in Neno, I wanted to understand the scope of this problem. How many people have resistant infections? How does this impact outcomes and mortality rates?

As it turns out, Limwado and some other researchers in Neno have been trying to answer these same questions. They have collected a data set of 269 samples from between June 2024 and June 2025 from select cases suspected of resistance. The samples come in a variety of forms including blood, cerebrospinal fluid, wound swabs and urine. Preliminary analysis found that 85, 72 and 62% of the samples contained resistant strains of E. coli, Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. One important note about these findings is that samples were only collected from certain severe cases that presented in the hospital. Optimally, this would be done on a larger scale with a more random assortment of samples; however, due to resource limitations this was not possible. Also, analysis of this data has not yet been completed or published, so findings are not yet finalized.

Research barriers

Limwado also spoke about some of the barriers to research in Neno District. Limwado explained, “The community doesn’t really know what all this research is all about. So I think we need to refine as well as to rethink and maybe observe them when we are preparing our proposals and our research ideas. Basically, I think engaging the community way from the beginning, so that they are in the know, [is important].”

Additionally, because most community members have only a primary or secondary education, researchers must design materials that are clear and accessible.

Data collection also presents a few challenges, and one primary reason for this is that most health records are kept physically — as opposed to digitally — for both the district hospital and primary care facilities. In District Hospital, this means that each department has their own paper register with patient data, so if a patient first presents at the outpatient department with a cough, then is sent to get a chest X-ray and then is sent to a specific ward for treatment, that patient’s data is now spread between three paper registers in three different locations in the hospital. Gathering and aligning all this data for research is both difficult and time consuming.

The landscape of Neno District also presents challenges. Getting to some remote villages in the district can mean hours in a vehicle each way, and many roads become treacherous or even impossible to traverse when it rains.

The way forward

Limwado emphasized that any long-term solution to antimicrobial resistance in Neno must begin at the community level. He and his colleagues are developing a district-wide education campaign that will involve outreach in village meetings, schools and churches, as well as radio programs to increase public understanding of antimicrobial resistance.

At the facility level, the team is piloting a clinical decision support tool to guide clinicians on when to prescribe antibiotics for respiratory infections, alongside efforts to expand access to rapid diagnostic tests.

And Limwado has no shortage of future research ideas. “There is a lot which we haven't explored and can be explored, and lessons can be shared with the rest of the world,” he said.

“If there are people willing to do research in antimicrobial resistance, we are open to welcome them, and we are happy to work with them on this issue,” Limwado said.

The issue of antimicrobial resistance and its consequences continue to grow each year, and research efforts like Limwado’s aim to better understand local drivers of resistance and inform practical interventions in resource-limited settings.