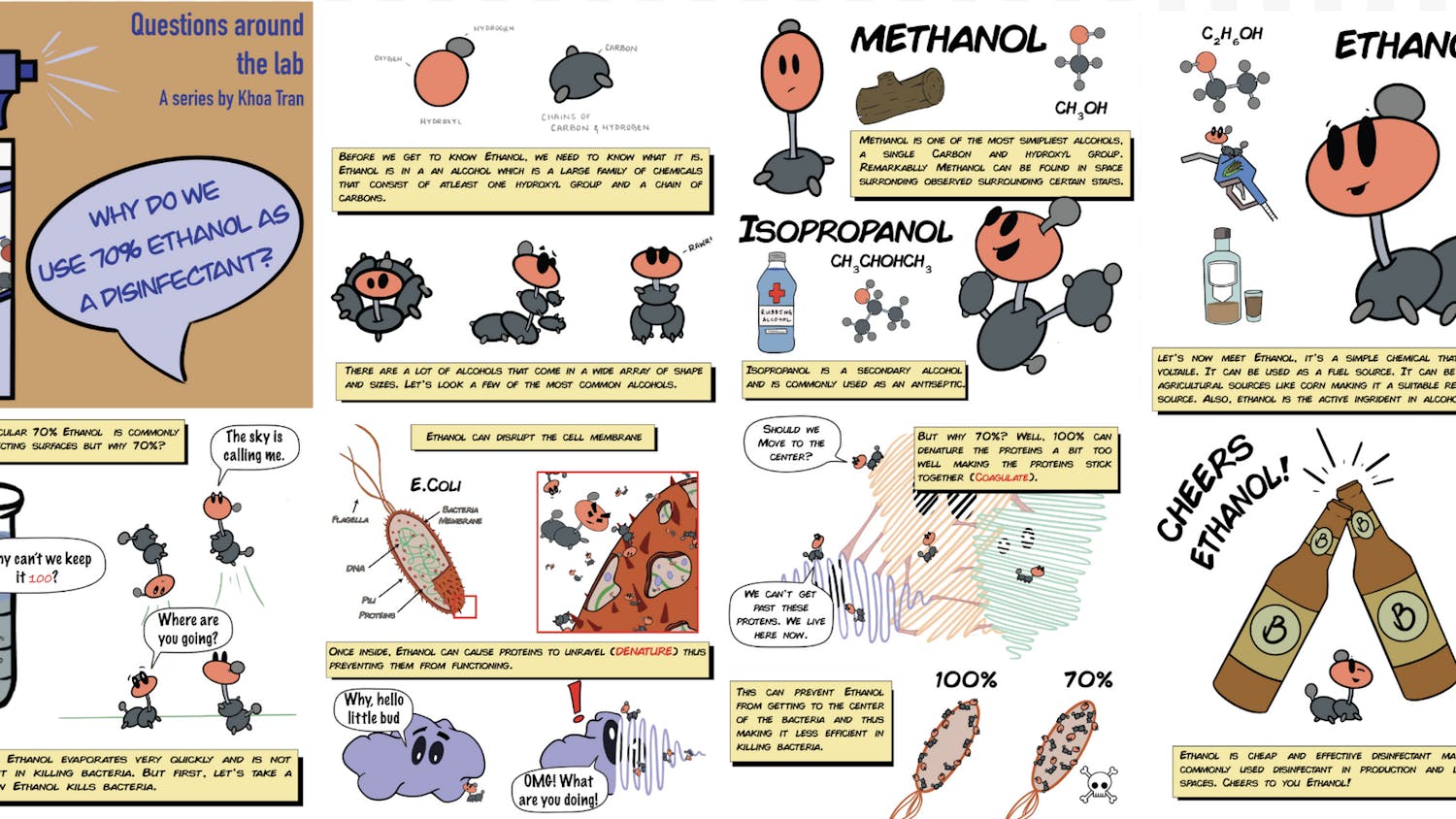

Throughout the past few decades, antimicrobial resistance has been on the rise as a result of increased antibiotic use. Like an arms race played out on a tiny scale, pathogenic microbes develop mechanisms to survive against the antibiotics used to kill them, rendering those antibiotics less useful in treating infections.

Situated at the top of the Biomedical Research and Public Health Building in Chinatown and with views overlooking the Tufts Medical Center, the Laboratory for Combinatorial Drug Regimen Design for Resistant and Emerging Pathogens aims to combat this issue head-on. With lab spaces for tissue cultures and hoods to facilitate safe work with pathogens, the LCDRD is designed with antimicrobial resistance research in mind. It also includes a common space designed to foster the interdisciplinary collaboration that the space intends to cultivate.

Professor Bree Aldridge — associate director and combinatorial treatment core director of the Levy Center for Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance, professor of molecular biology and microbiology at Tufts University School of Medicine and professor of biological engineering at Tufts University School of Engineering — underscored the necessity of the space. “The concern about [antimicrobial resistance] is appropriately growing, and so I think it’s very timely that we finally have a space here at Tufts to work on this,” she said.

While CIMAR has existed since 2019, what the group was missing was a space for collaborative work on projects between labs, academic partner organizations, clinicians and industry partners.

Dr. Kathleen Davis, CIMAR scientific team lead, highlighted the necessity of interdisciplinary antimicrobial resistance work. “I don’t have training as an MD,” she pointed out. “I don’t bring that clinical perspective.” With the use of CIMAR’s collaborations and the LCDRD space, however, she can speak regularly with clinicians and design more useful experiments, informed by that clinical perspective.

With Tufts Medical Center right across Harrison Avenue, the partnership between CIMAR and the medical center aids in obtaining isolates for research and working with clinicians who can provide valuable context. CIMAR also holds existing partnerships with other academic institutions and other Tufts institutions, like the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine.

With the opening of the LCDRD, there is the additional goal of facilitating collaboration with industry partners, who are looking for the space to outsource their combination drug studies (using more than one antibiotic in treatment), for example. First, however, Davis acknowledged the need to get the space up and running with projects in order to demonstrate the workforce capacity of the space. An ongoing project will examine the ability of Klebsiella pneumoniae to adapt its defense against antibiotics in different environments.

Klebsiella and current projects

Klebsiella, while it may not be as well-known as antibiotic-resistant bacteria like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is a highly opportunistic infectious agent and can pop up in many different infection types. “It’s definitely a concern for neonatal infections,” Davis said, comparing it to an Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Enterobacter pathogen. According to Davis, “Klebsiella is very very good at adapting its physiology to grow in different environments.” This makes the bacteria also very good at acquiring resistance to different drugs. The way that Klebsiella may react to antibiotic treatment differs in the lungs, where there may not be many amino acids available, as opposed to the bloodstream or the urinary tract, for example.

With this in mind, researchers like Davis are looking to study the ability of the bacteria to resist different drugs in media designed to mimic different conditions in the body. “We need to essentially develop lab recipes,” Davis said. Researchers will pair this in vitro work with mouse models to study the in vivo component.

Currently, there’s very little consistency when it comes to combination-testing different drugs and a lack of research looking at how combinatorial drug treatment is affected by bacterial infections in different environments in the body. While some bacteria don’t seem to differ much in their ability to resist antibiotics in different locations, Klebsiella in particular can have dramatically varied responses.

“It was very important to take into account the growth condition, and the implication would be: Different therapy might be more appropriate in different infection spaces,” Davis said. Understanding the responses of bacteria like Klebsiella to antibiotics not only aids in clinical spaces, as Davis points out, but also in the antibiotic development pipeline. Early antibiotic development involves a great deal of in vitro work, and the ability to test different compounds in media mimicking different environments in a consistent and controlled manner could be extremely beneficial.

Two features make the LCDRD uniquely poised to tackle this kind of work. One is the presence of the so-called ‘drug printer,’ quite literally an HP printer that can dispense nanolitre amounts of drugs into 96- or 384-well plates. This ensures that the combinatorial drug testing can be done at high throughput.

The other factor is the Diagonal Measurement of N-Way Drug Interactions platform, originally designed by Aldridge. The most widely used screening method in combination drug testing is called the checkerboard assay, which can test differing combinations and levels of drugs against each other. Usually done in a standard 96-well plate, this method presents problems when working with four-way drug combinations, for example, as Aldridge does in her work with tuberculosis. If working with a four-way combination treatment, a researcher would need twenty-five 96-well plates to test all combinations.

“We just took an engineering approach to this and hacked the checkerboard assay,” Aldridge said, describing the DiaMOND platform, which uses only one 384-well plate to test up to five different drugs in all combinations. The DiaMOND platform would not be usable as a high-throughput screening method, however, without the use of the drug printer, which can accurately deposit the precise nanolitre amounts needed in each well.

Altogether, the LCDRD is poised to aid scientists like Aldridge and Davis in their research, as well as collaboration with other academic institutions, industry partners and clinicians.

Antimicrobial resistance today

In imagining a world rife with drug-resistant pathogens, spaces like hospitals could become dangerous to individuals with or without active infections. Routine infections like those caused by Streptococcus bacteria could become very difficult to treat, or at the very least more difficult to live with.

There are other concerns, too, especially concerning antimicrobial resistance in livestock populations. Infections in livestock populations that impact the ability of them to be used for food or that kill off large numbers of livestock could be dangerous. It could result in rising food prices or make food more difficult for people to obtain. Regardless, antimicrobial resistance in all formats will impact vulnerable populations the most.

So what motivates researchers to work on projects like these?

“The goal and hope [is that] we would be able to push this all the way to clinical translatability,” Davis said. “The idea that something I’m doing on a Tuesday afternoon could … provide information that clinicians could use to make life less uncomfortable for someone. … We’ve got a chance to make life more comfortable and give them more time with their family.”