“A Life Illuminated,” a 2025 documentary by Tasha Van Zandt about famed marine biologist Dr. Edith Widder (J'73), premiered for Boston audiences on Oct. 22. The historic Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline hosted the first evening of the 2025 GlobeDocs Film Festival, an annual event premiering documentaries produced by The Boston Globe. A Q&A session with key players in the documentary filming process followed the screening.

Van Zandt captured the extraordinary life and accomplishments of Widder through a mirage of stunning visuals. From footage of color-changing squid to bioluminescent marine snow, the visuals in “A Life Illuminated” reinforced the otherworldly aspect of the deep sea.

In the Q&A session of the film screening, Van Zandt and producer Sebastian Zeck got candid about the filming process, discussing the experience of getting to dive in a submersible during the shooting of the film. They mentioned the challenges of the limited diving time and sensitive camera, which, coupled with the pressure to get the perfect shot, made for a unique filming experience.

Widder is no stranger to filming in demanding environments. In 2012, she was the first scientist, along with a team of researchers, to film the giant squid in its natural habitat. This historic discovery landed her on the cover of numerous national publications and television productions, garnering the attention of people worldwide.

Van Zandt was among these onlookers, revealing in the Q&A session that the video inspired her to make a film sharing Widder’s story.

Widder, a Tufts alum, is renowned in the field of marine biology for her contributions to the understanding of bioluminescence — the production of light energy triggered by a chemical reaction in an organism’s body. A beautiful yet elusive phenomenon, there is still much left to be understood about its unique role in deep-sea ecosystems.

Towards the start of her career, Widder remarked how one used to be able to “pick up a marine biology textbook and find no mention of bioluminescence.” The film takes the viewer on a journey through Widder’s lifetime of scientific accomplishments, surveying the contributions she has made toward the field as a whole.

Widder earned a Bachelor of Science in Biology from Tufts University, a Master of Science in Biochemistry and a doctorate in neurobiology from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

She worked as a senior scientist for many years at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute in Florida. In 2005, she founded the Ocean Research and Conservation Association, which aims to tackle marine ecosystem degradation and use technology to grapple with complex scientific issues. Widder has remained committed to ORCA and its mission since its foundation.

Widder has made great contributions to the field of submersible science, completing over 250 dives in Johnson-Sea-Link submersibles and spearheading the creation of innovative submersible instrumentation.

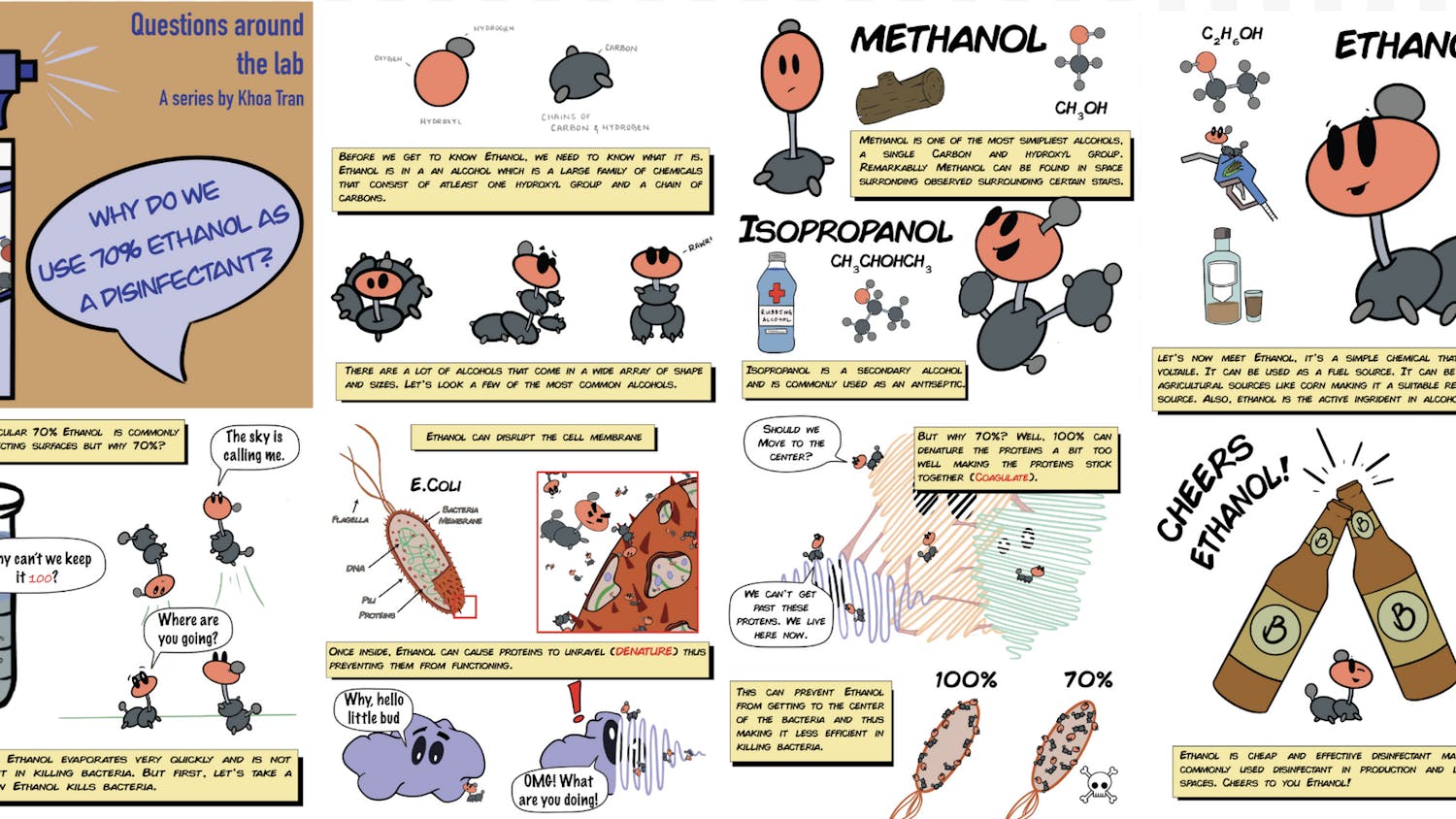

Perhaps one of her most outstanding achievements is ORCA’s Eye-in-the-Sea, a remotely operated deep-sea camera system that can detect and measure the bioluminescence of marine organisms. According to ORCA, the EITS “uses low-light imaging in combination with far-red illumination that is invisible to most deep-sea animals.” With EITS, Widder has been able to document a myriad of marine life, from bioluminescent jellyfish to giant squid, most famously.

Her EITS enabled her team to capture the first-ever footage of bioluminescence. In the film, Widder mentions that she was driven to share the experience of viewing bioluminescence with the world, something that would otherwise be limited to a finite group of people who could access submersibles.

The EITS was also what enabled Widder to record the famous squid video. She devised a plan to attract the squid with ‘e-jelly,’ an optical lure that resembles a jellyfish and can imitate bioluminescent displays. The lure can imitate the bioluminescent patterns of the common deep-sea jellyfish Atolla wyvillei, in turn attracting predators such as the giant squid.

From the very start of the film, viewers are captivated by the suspense surrounding the outcome of Widder’s latest expedition. Exploratory by nature, Widder sought to understand the evasive ‘flashback phenomenon.’

When diving, she’d noticed that when she’d flash the submersible lights out into the water, the bioluminescent organisms would flash back at her. She has observed this phenomenon many times over the course of her career but has never been able to record it.

Obtaining a video of the flashback phenomenon was Widder’s research aim when she took Van Zandt and Zeck down in the submersible during filming. However, before revealing the anticipated experimental results, the film takes the audience on a journey through time.

Widder spent her formative years at Tufts studying biology. As a female scientist, her mother, who had received a doctorate in mathematics from Bryn Mawr College, served as Widder’s greatest inspiration as a scientist: “And so, with her as a role model, I just, you know, had a very strong sense that women could do anything they wanted to do,” Widder said.

Thus, she never let her gender deter her from pursuing a career in academia. Instead, she reminisces on the professors who had the most influence on her, such as Ned Hodgson, former professor and chair of the biology department at Tufts.

She recalls him describing in a lecture what it felt like to “discover something that nobody had ever known before in the history of the world.” Widder said that by the end of the class, she “was on the edge of [her] chair” and knew that someday she wanted to feel that same way.

And she certainly did — over the course of her career, Widder has been the first person to observe many phenomena, from the flashback to the recording of the giant squid.

This did not come without challenges. “You end up having to make compromises that are difficult,” Widder said. When funding agencies would ask her what she was going to find, she aptly responded, “I don’t know. That’s the point.”

She noted she often had to “[walk] a fine line to be able to get the funding,” especially when the nature of her work is so exploratory.

When asked if she had any advice for aspiring marine biologists, Widder advised undergraduates to become an expert in the specialized field that they are most interested in. When it comes down to a highly selective sea-faring expedition, she stressed that students should take openings where they can find them.

Whether this gap be in molecular genetics, acoustics or spectrometry, Widder maintains that there are numerous ways for students to become involved in marine biology. She believes that this specialization will ultimately “get you on the ship a lot faster than just a very broad background in marine biology.”

Widder’s specialization in instrumentation is what has enabled her to share the wonders of bioluminescence with the world. Thanks to Van Zandt’s suspenseful cinematography, viewers sat with bated breath as they watched Widder try to capture the mystifying phenomenon.

After a series of painstaking failed attempts, the screen finally illuminated with bioluminescence, the blue and purple sparkles of light indicative of Widder’s success.

The film not only retells Widder’s life of discovery but also takes viewers on an immersive experience through the trials and errors of scientific exploration. By the time the audience views the flashback phenomenon at the end of the film, they feel as if they’ve gone through all of the emotions with Widder: curiosity, fear, excitement and, ultimately, satisfaction.

“A Life Illuminated” shines the spotlight on the deserving Dr. Widder, finally illuminating to audiences worldwide her immense dedication and contributions to the marine sciences.